Metaphysics Of Architecture

Experiences of an Architecture Student

A pole, is a column, is a tree.

A building, is a mountain, hides a cave.

-prologue-

Ainsi toute la Philosophie est comme un arbre, dont les racines sont la Métaphysique, le tronce est la Physique, et les branches qui sortent de ce tronce sont toutes les autres sciences.

René Descartes, From a letter to Abbé Claude Picot

I wonder if this parable can be applied to architecture? Would the trunk of this tree represent nature? And would the branches represent the entirety of architecture, with all its different formal phenomena and stylistic expressions? If so, nature would not be the last link in this chain. There would exist something even deeper: the root, the metaphysic fundament, inherent in nature as well as in architecture, which nourishes the architecture by permeating nature.

If thinking sets out to experience the basis of metaphysics, to the extent that such thinking tries to think the truth of be[ing] itself instead of only formulating be-ing as be-ing, it has in a certain way abandoned metaphysics.

Martin Heidegger, What is Metaphysics

-I-

It is an afternoon in late July, and I am on a walk. The fields spread out under an endless sky spanning the Lakeland of the Duchy of Lauenburg. The sun is about to break through a dramatically rugged cover of clouds, which slowly drifts above the land, dividing the world in light and shadow. In the distance, I discover a pure white heap of lime and next to it another, but significantly smaller one. They are connected through a trace of lime which results from removing part of it to fertilise the fields. The two heaps seem to form a compositional unity in the midst of the vast green of the grass. The white of the lime is all white. It is almost blinding you, as soon as a sunbeam hits its surface. I am walking towards the two heaps, which serve as a context to one another like duomo and battistero. They kind of create a centre of gravity in the endless expanse of the fields and the sky.

While getting closer, it seems to me, as if I could feel the presence of the material with my own body. Its weight seems to rest in itself. Past rainfalls have transformed the outer layers of the lime into a coherent surface and gave the heaps a monolithic appearance. The two „lime bodies” are no bigger than you. I sit down in the grass and watch them.

Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.

Le Corbusier, Vers une Architecture

From this angle, I see the clouds dramatically burst above the greater heap. As if clouds overflow a mountain’s peak they stream above the little massif. The natural forces project a show of light and shadow onto the surface of this massive body, by shoving the clouds against the sun, which is breaking through the clouds.

It appears to me as if I could inhabit this mountain and I get very close to it and I take perspectives which intensify this impression.

From this close, little lumps leached out from the surface appear like huge rocks. One area with a rough terrain expands to a large boulder field, and the clouds stream above the mountain and me.

I am on a completely white mountain amidst the Lakeland of the Duchy of Lauenburg.

-II-

Actually, however, life begins less by reaching upward, than by turning upon itself. But what a marvellously insidious, subtle image of life a coiling vital principle would be!

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

If you go for a walk in the park of the Charlottenburg Palace, you can experience nature on various levels of organisation. Starting at the palace and moving northwards, you travel through a continuum of slowly dissolving order, until the park resembles a seemingly untouched natural environment. Here, it is most likely that you will run into a squirrel, heron or sometimes even a fox. Alongside the initially orthogonal, slowly more and more meandering paths, the trees are standing, as if it was the most usual thing.

It is a prejudice of the one-sided constructive understanding of architecture if you take roof and ceiling for the main elements instead of already recognising the “Umwandung” (walling) as spatial design by itself.

August Schmarsow, Der Werth der Dimensionen im Menschlichen Raumgebilde

At first, they are simply trees to you, at best, defining the area in which you are supposed to walk in. Focused on the point at the very end of the trail where all lines meet, you perceive the trees only as a peripheral phenomenon. But it is almost certain that due to a particular phenomenon one of these innocent bystanders will attract your attention at some point. You start to look for this phenomenon also at the other trees. What you don’t notice, while investigating this one phenomenon, is that you compare it with a lot of others at the same time. And while you compare this one with others you incorporate them all. Maybe you are impressed by a massive trunk or the way one tree is joined with the ground. You survey its surface – the bark. You discover that it is elaborately structured by following some kind of principle. You discover that the trunk is not uniform, not an ordinary pillar in a shopping mall, a differentiated body part, evolving in thick strands from the ground. Something seems to pull on it. And as you look at the whole tree again, you are not so sure anymore, if it stands heavy on the ground or if it is clinging to it in order to not be ripped off.

The matter is heavy, it is pushing downward and wants to spread over the ground without any form. We know the violence of gravity from our own bodies. What keeps us upright, prevents us from a collapse into shapeless form? The counteracting force, which we may call will, life or whatever. I call it “Formkraft” (Shapeforce). The contrast between mater and form, which moves the entire organic world, is the basic theme of architecture [. . .]. We find the will to take shape and to overcome the resistance of a shapeless material in every-Thing. [. . .] Everywhere we find this upward pull counteracting the weight, usually finding its ultimate expression in a conoid shape.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur

And now you see that even if the trunk of the tree is almost vertical it is not growing straight upward. Using all its strength, pulling on the inner fabric of its material, while pushing against the forces of gravity, it winds up around itself towards the sky. And while looking at the other trees around, you realise that it is only one tree among many clockwise and counterclockwise twirling trees.

-III-

I am in the north of Italy. It is summertime. Travelling by car heading to the Valstrona close to the Lago d’Orta. On my way to Omegna, a city at the northern tip of the lake, I first pass through another relatively vast valley, driving on a broad highway. The road finally leads right through the small city. In the centre, I turn right and cross a bridge in the west of the city, which takes me beyond the Strona river and out of Omegna again. Right after crossing the bridge I have the feeling that this bridge was the eye of the needle for the thin thread on which all the villages of Valstrona are hung one after another. While driving further into the valley the mountain ridges seem to sneak up to the road until it gets pushed upwards under the enormous pressure. The weather in this valley is different from the one down by the lake. While looking through the rear window where the sun is dancing on the lake’s surface, thick, wet clouds are sinking down the mountain ridges in front of me, like old men in their armchairs. I have the impression to immerse into a different, mystic world. From time to time the vegetation reaches far above the street and forms natural tunnels. I pass some seemingly abandoned sawmills, pass through tiny villages which never consist of more than ten houses. I am meeting Nobody. Sometimes, alongside the narrow road, rusty electricity pylons appear from the depths of the valley and after the next curve, they dive down again, to a ground which I am not able to see. Along the roadside, in front of a shed rests a wooden boat on a wooden scaffold. It seems strangely out of context in front of the backdrop of the valley and adds a surreal touch to the whole scenery. The Valstrona is an enchanted valley.

[. . .], and by changing the space, by leaving the space of one’s usual sensibilities, one enters into communication with a space that is psychically innovating.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

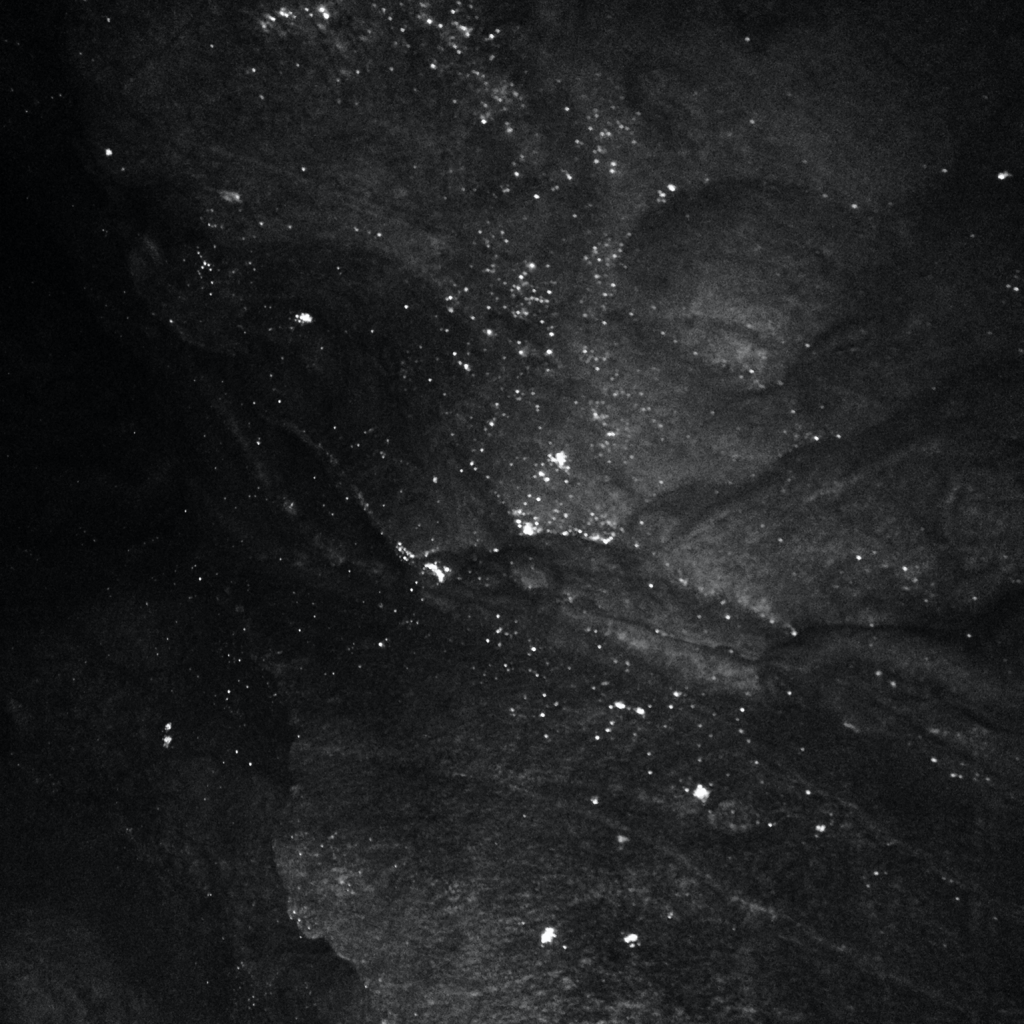

I am arriving in the small mountain village of Marmo. Here I am meeting with the geologist Enrico Zanoletti, who will guide me into the Grotta delle Streghe – the cave of witches. After a short introduction about the history of the cave, which was found by accident during the excavation of marble in the 19th century, we walk down a narrow path on the slope down to the bottom of the valley. We cross the Strona on a bridge which convinces through its simple construction of two steel beams and rectangular grating panels. On the other side of the river, we walk up a slope again until we are finally standing in front of the break-off edge of the marble quarry. The entrance is covered by vegetation. Holding on to a rope we descend into the cave on its ground a small trickle ripples. The cave walls are humpy but very smooth, ground by the water. While descending we have to be careful to not slip on the wet surfaces. In the first chamber, I can stand upright, but from here we will have to move on mostly crawling. We slip through openings which are barely big enough for our bodies. Actually, it isn’t a really uncomfortable way of locomotion, because the cave – although from marble – gives you the impression one could lie down to sleep anywhere. We arrive at a small chamber in with we can sit. The cave’s ceiling which is vaulting us is covered with a fine dust which is sparkling in the light of our headlights. Like a starry sky at a clear night and the cave encloses us save and soft under this peaceful “night sky”.

It also has a vaulted ceiling, which is a great principle of the dream of intimacy. For it constantly reflects intimacy at its centre.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

In the pale light of my headlight, I am crawling through a narrow tunnel made from marble, of which I can not see the end. It is that tight so that movement is only possible in one direction: forward.

Finally, the rock squeezes me inside another chamber. A frieze of rhythmic waves, carved by the force of water is decorating the upper part of the cave’s wall.

The tones of the music would have no meaning if we did not regard them as an expression of any sentient being. This relationship, which was a natural one in the original music, the singing, has been obscured by the instrumental music but has not been abolished. We always interpret the sounds we hear, as the expression of a subject and we do the same in the world of bodies. The forms become important to us only because we recognise in them the expression of a feeling soul. We involuntarily bring every Thing to life.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Prolegomena zu einer Psychologie der Architektur

We get to the next chamber by moving across some rocky columns, crawling like two giants through a medieval vaulted cellar.

After this follows a passage where we can move upright but well enclosed by the marble cave walls. We squeeze our bodies through a tight slit. In comparison to the other chambers, this one seems almost banal. It is a circular space with a slightly vaulted ceiling. Its surface is like in the other chambers humpy and very smooth.

„The exterior of the aforementioned chamber,“ wrote Palissy, „will be of masonry made with large uncut stones, in order that the outside should not seem to have been man-built.“ Inside, on the contrary, he would like it to be as highly polished as the inside of a shell [. . .] He wants the walls that protect him to be as smoothly polished and as firm as if his sensitive flesh had to come in direct contact with them. The shell confers a daydream of purely physical intimacy. Bernard Palissy’s daydream expresses the function of inhabiting in terms of touch. [. . .] , the real home of this man of the earth was subterranean. He wanted to live in the heart of a rock, or, shall we say, in the shell of a rock.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

We switch off our headlights and it is completely dark. This darkness does not acknowledge the existence of light.

I lie flat on my stomach on a stony hump. And my idea from before – one could comfortably lie down almost everywhere in this cave – seems to be validated at that moment. In this dark cave with its humpy-smooth surface, every positive of one’s body seems to find its negative equivalent. In the darkness, space seems to expand endlessly. The echoing drops of water seem to be the only material things in this infinite space, defining fixed positions by the sound of them touching the ground. And in my spirit is hovering backwards along the way we came here. Through the chamber with the frieze, underneath the starry vaulting and up into the light, through the entrance hole, back through the valley which is tight and widens gradually with the increasing distance to the cave. All together one single immense space. It almost seems to me if the whole valley culminates into this cave.

Often it is from the very fact of concentration in the most restricted intimate space that the dialectics of inside and outside draws its strength. One feels this elasticity in the following passage by [Rainer Maria] Rilke: „And there is almost no space here; and you feel almost calm at the thought that it is impossible for anything very large to hold in this narrowness.“

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

The light is falling through the entrance of the cave, like through an oculus of a cupola.

And when I find myself later that day in Como, inside the cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, with its high-rise vaultings, the massive and slick stone-piers, the huge opening of its portal which is only covered by a curtain softly floating in the warm winds, directing my eyes into the blinding light, then I find myself back inside the slick, humpy and safe cave.

-IV-

On the Via della Conciliazione

… thoughts towards an Architekturnatur.

To my left and my right facades of homogeneous colour tones rising steeply like rock faces of a small canyon. The window openings are closed with the typical Italian brown or green wooden shutters which you can open like a wing door while the lower part can be flipped outward.

In the distance the enormous silhouette of Basilica di San Pietro. The sun is burning mercilessly down on me and a group of pilgrims in neon yellow safety vests. Only the small obelisks alongside the road are casting narrow shadows in which people seek shelter from the brutal heat. The scenery almost appears like a desert landscape to me where withered trees represent the last refuge from the piercing beams of the sun. At the end of this canyon of buildings, I am finding myself in the centre of a great glade, surrounded by Berninis gigantic petrified trees.

The sacred grove was by no means a substitute for the temple: the wood was the temple, its trees the columns and the firmament its roof. The word „templum“ signifies a … piece of land dedicated to godhead, a holy precinct. Most houses of god betray their vegetable origins by being oriented, and opening up to the sun. Thus what we call a temple is actually an abstraction of a grove, the thicket of columns recalls the thicket of trees.

Bernard Rudofsky, The Prodigious Builders

On each side of the oval plaza life-giving water wells up from stone fountains. But to my disappointment, they are out of reach behind several fences. In the centre of the plaza stands the great obelisk, which was erected under the supervision of Domenico Fontana like a giant dead tree. Some people are seeking shelter from the sun in its not to opulent shadow. St. Peters Cathedral raises in front of me like a sandstone massif. At this moment I urge to reach it as soon as possible, mostly because of the heat. Finally arrived inside the cool walls I see the great vaults which are spanning above my own and the heads of the many people visiting the sight. The interior appears like an enormous cave to me. A cave with painted walls and vaults, an image we know from the very beginning and which had seemingly been stored in our collective memory.

A canyon, a glade, a mountain, a cave. Nothing extraordinary in the first place but it is not a piece of land occupied for a particular purpose. Everything is built by people at a location of their own choice. And what the sounds are to Bachelard, are the shapes and materials to me.

When insomnia, which is the philosopher’s ailment, is increased through irritation caused by city noises; or when, late at night, the hum of automobiles and trucks rumbling through the Place Maubert causes me to curse my city-dweller’s fate, I can recover my calm by living the metaphors of the ocean. [. . .] In fact, everything corroborates my view that the image of the city’s ocean-roar is in the very „nature of things,“ and that it is a true image. It is also a salutary thing to naturalize sound in order to make it less hostile.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

-V-

In a valley in Switzerland – called Valle Verzasca – exists a small restaurant. A narrow stone staircase leads the way from the terrace up on a small slope. At the end of the staircase, a narrow trail is pushing past a bunch of grapevines. Following the trail, you reach a tiny grove. On the left hand, the rock falls steeply into a canyon. To the right, a forest is covering the mountainside. Down in the canyon runs a cold, blue-green creek nourished by a small waterfall which cuts off the trail. A small mountain village is sitting on a rock on the other side of the canyon. And on the edge of the slope, alongside the trail, there is just now a little fragile whim of nature to observe. A little phenomenon, banal but astonishing at the same time. On top of a small boulder, a structure has been formed by a tiny landslide and the magnificent creativity of water. The water has washed away parts of the soil and left behind a collection of small clay towers on top of the boulder. If you squat you get the right perspective. A small city all from clay on a boulder. And opposite to it a mountain village all from stone on a rock.

With an „exaggerated“ image we are sure to be in the direct line of an autonomous imagination.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

A tiny casual natural phenomenon can transport us from one distant country to another even more distant country only through inspiration, triggered by formal analogies. And because I know that image of that city from clay in Morocco and because I have to imagine its interior it is happening very naturally to me that I also can imagine an interior of this miniature of a city made from clay. And I can almost see me walking in the street of this city which is winding up the hill. I can vividly imagine myself into the miniature and leave Switzerland for a moment without leaving Switzerland.

It is as though the miniaturist challenged the intuitionist philosopher’s lazy contemplation, as though he said to him:

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

„You would not have seen that! Take the time needed to see all these little things that cannot be seen all together.“ In looking at a miniature, unflagging attention is required to integrate all the detail.

And so there is, beyond the river, in opposition to the small mountain village in Switzerland a far distant Moroccan city made all from clay. And the scale increases the distance.

-epilogue-

During my journey throughout the world, I have never made a categorisation of what is looked at. I always looked at all buildings, pillars, spaces, vaults, caves, columns, mountains, stumps, and heaps with the same attention and the same sincerity. All these things aroused my interest in the same spontaneous, impulsive way. However, as I looked at things with constant indifference, I did not give them any definitions and no truth about what they are. I just looked and in result, I could concentrate on how they were, the things I looked at. I stayed with them in that moment of enduring the being. It is a kind of looking at things which can maybe be described as a mixture of platonic excitement and stoicism in the sense of a Democritus, without the amazement about seemingly extraordinary things. A kind of indifferent amazement about the ordinary as well as about the extraordinary.

To say a column is a tree is only possible for me, if I accept this as one truth among many others, without questioning it further on. It is a reversed abstraction and therefore multiplication of phenomena. Every time while looking at architecture this idea brings me back to the mountain, the tree and the cave. It brings me back to very original and natural spaces and spacial structures.

I think that the natural phenomena causing very direct, immediate and original emotions inside us humans. A look on architecture inspired by the tree, the mountain and the cave can have a positive effect on architectural practice, as well as on the reception of architecture – and most important of all – on the human mind, soul, and body. That is why I consider natural phenomena the basis of my designs.

Metaphysics Of Architecture, Experiences of an Architecture Student

Alexander Johannes Heil

Berlin 2017